Big data is a concept that arrived with an appropriately enormous amount of hype. We all know the digital age has generated huge amounts of information and that this mountain of data is especially prominent in the financial services industry. But the ways in which this avalanche of detail is being exploited are many and varied.

Carmine Gioia is a visiting professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Although he is a resident of Copenhagen, the Italian academic spends a lot of time in the United States working with MIT’s Big Data Initiative. This is not abstract research as his work bears fruit in the world of investment banking where Professor Gioia also operates as chief data scientist at Denmark’s Saxo Bank.

Saxo Bank has 27 offices worldwide trading currencies, stocks and bonds. Professor Gioia is concerned with learning how to give Saxo’s clients the best possible experience when they deal with the bank. Every time they log on to the bank’s website their clicks are analysed to try and work out just what it is that would most meet their needs.

“We want to make the experience of dealing with the bank as relevant to them as possible, so we can offer them information based on their previous search options,” says Professor Gioia. He is dealing with what he terms “rich data”, information that flows from multiple sources including social media. The algorithms Professor Gioia and his colleagues devise are intended to pull out trading options that dovetail exactly with the personal profile of each client.

The key to the boom in data analysis is that analysing information has become cheaper. Cloud computing allows banks to store and assess data at infinitely lower rates than was previously possible. But this brings its own risks. If an institution doesn’t give enough thought to how it goes about this exercise, it can still get overwhelmed with information that stifles decision-making. “Big data can mean paralysis,” Professor Gioia cautions.

ANALYTIC PROGRAMS

US software business Birst writes analytic programs that take data and pull out valuable insights for clients such as the Royal Bank of Canada in Toronto. Southard Jones is in charge of product strategy at Birst and points out that tasks which once required scarce skills are now accomplished by the software his business rents to clients over the internet using the cloud model. “In the past you needed data scientists to run the algorithms for data analysis. Hiring them was very expensive,” he says.

Today Birst can analyse the characteristics of account transactions and queries using 40 different aspects of a customer’s behaviour, and identify the most profitable customers its banking clients should concentrate on.

The economics of this data analysis operation are best understood in the context of data science costs. Birst can run a data analysis project for a bank for between £100,000 and £500,000. The dedicated software packages that banks once employed for data analysis could cost well over £1 million and the accompanying team of data scientists could expect to earn more than £100,000 a year each.

If these figures illustrate how data analysis costs have plummeted, the other side of the coin is the explosion in the scale of the data that needs analysing.

SHARP CURVE

Kx was founded in 1993 to address the single problem of how to explore and exploit mounting quantities of data held in computer systems. The technology available to the financial services sector then is antiquated by the standards of an online world where millions of people check their bank balances using mobile devices. Simon Garland, a British mathematician who is chief strategist with the US company, talks of how data volumes have risen in a very sharp curve.

The key to the boom in data analysis is that analysing information has become cheaper

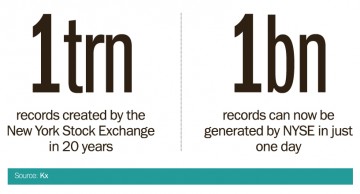

Citing records, each of which represents one trade or price quote, he describes the kind of information the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) generates. “Since 1993, the NYSE has created one trillion records. But that volume started relatively low and then rose sharply from the late-1990s onwards. Today the NYSE can create a billion records in just one day,” he says.

Kx collects massive amounts of data and then presents it in a way that other systems, such as data analysis programs, can work on. “We provide a very, very fast data base so people can act on interesting movements in the market,” says Mr Garland. Speed is of the essence in the world of trading systems and Kx is the high-performance engine that keeps a whole raft of other clever software products on the road. The velocity at which Kx works reflects the fact that traders need to react to events inside seconds.

The reach of big data work extends from the giddy activity on Wall Street to high street banks in the UK. Harvey Lewis, research director at business advisers Deloitte, explains that financial institutions have an appetite for analysing customers however large or small they may be. “The point about big data is that you can use it to understand your customer, and target them based on what products and services they really want,” he says.

The traditional bricks-and-mortar bank branch can be just as important to sophisticated data analysis exercises as any amount of online interaction, according to Mr Lewis. “Physical and online presences feed off each other. The branch can drive more digital business,” he says.

Combining data gathered on the internet with details of customer transactions in the bank branch is a rising trend. For financial services, there is no end to the data that can be profitably analysed.

ANALYTIC PROGRAMS