Sixty metres below London, engineers are building a £4.2‑billion, 15-mile super sewer, designed to prevent overflows of sewage from spilling into the River Thames. The project is one of hundreds of schemes, from broadband to high-speed rail and power stations, aimed at renewing the UK’s creaking infrastructure.

The Thames Tideway Tunnel is controversial, not least because it is a test case for how private finance is used. The company is owned by a consortium of infrastructure funds, using money from pension schemes and other long-term investments, to keep it off the balance sheets of both Thames Water and the government, even though it is being paid for through higher consumer bills.

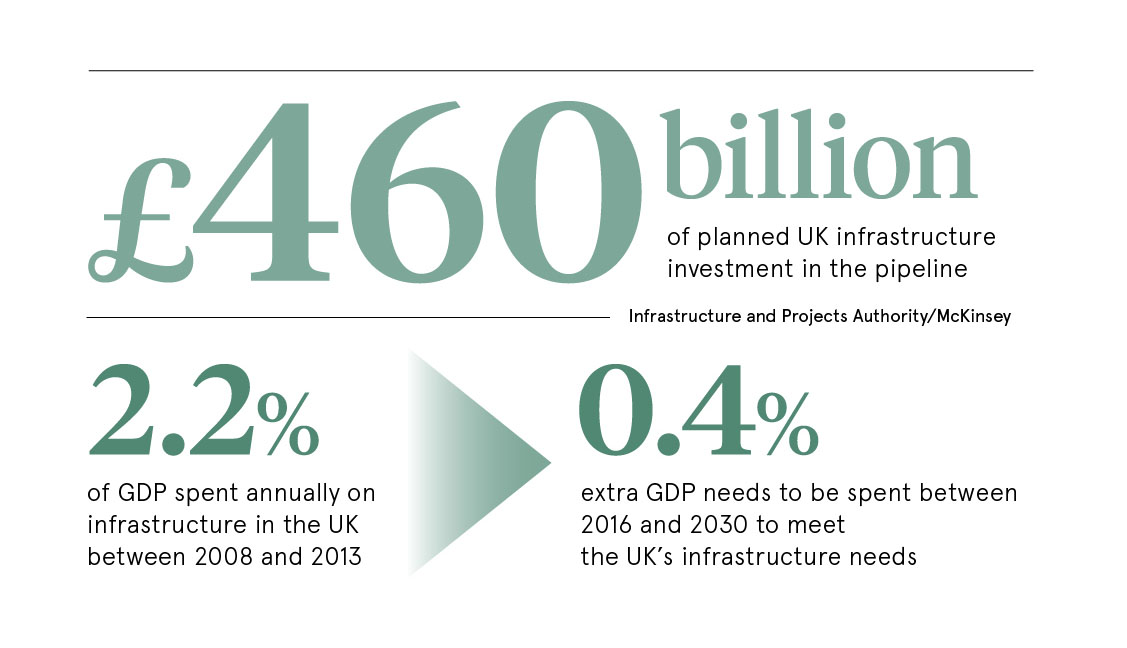

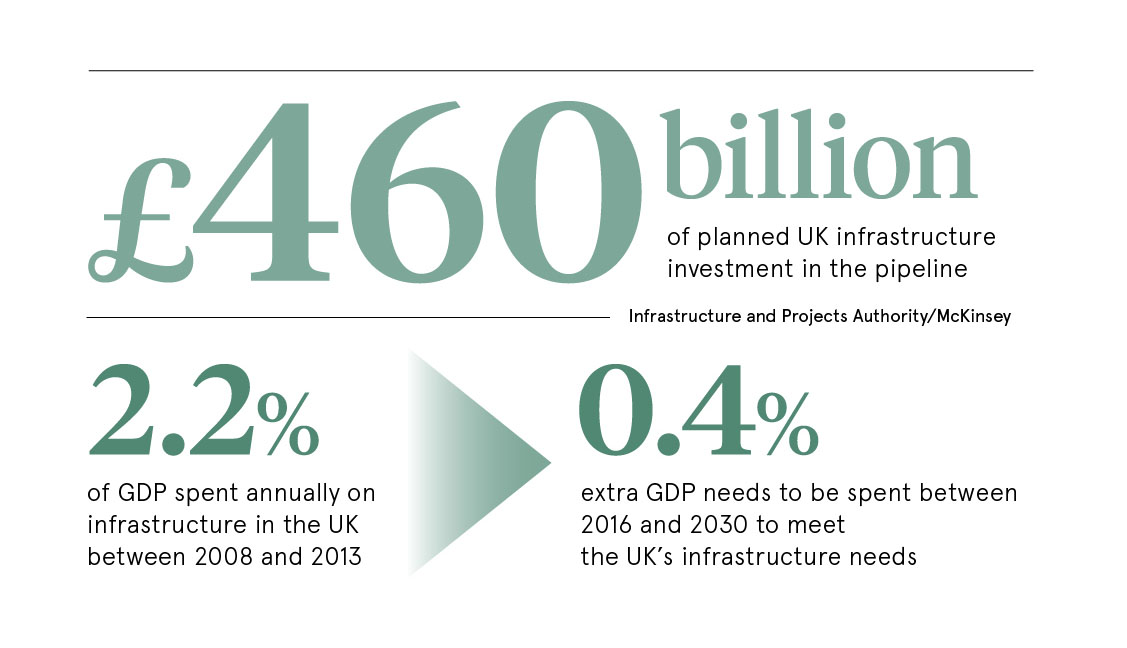

The government plans more than £460 billion of infrastructure investments over the next few years, with almost half financed by the private sector. That is ambitious, especially as the political climate has led to greater questioning of the value of private sector involvement in public services.

The UK pioneered privatisation and outsourcing 30 years ago. Now, however, the Labour opposition wants to renationalise energy, rail and water companies, halt the use of private finance initiative (PFI) contracts and bring some existing schemes back in-house. The collapse of Carillion, the construction company undone in part by overruns on PFI projects, has added an extra twist.

Even the Conservative government, which supports private finance, is sensitive to concern about excessive profits. It proposes, for example, a cap to end “rip-off” energy prices.

If we remain constrained, the country will be much the poorer for it 30, 40 or 50 years out

So far, political risk appears not to have significantly harmed infrastructure investors’ willingness to invest if projects are structured attractively. The UK has prided itself on being open to the world. Foreign direct investment has brought benefits including capital, jobs, ideas, talent and leadership. But on top of Brexit, this adds another element of uncertainty.

Few doubt the UK needs to upgrade infrastructure. It has spent less on this than other developed countries over the past three decades, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The result is overcrowded trains, congested roads and choked airports.

“We’re on a positive trend, but we have got a long way to go,” says Richard Threlfall, global head of infrastructure at KPMG, the professional services firm. “We have an inheritance of roads and sewage systems and power systems, many of which date back to the middle of the last century and require significant amounts of investment.”

The UK spent 2.2 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) annually on infrastructure between 2008 and 2013, according to McKinsey Global Institute, below Japan, Canada, Italy and the United States, but slightly ahead of France and Germany. McKinsey reckons the UK needs to spend an extra 0.4 per cent of GDP a year between 2016 and 2030 to meet its needs.

The government is raising its capital spending, but also needs private finance. Alongside state projects such as London’s Crossrail and the High Speed 2 (HS2) north-south rail link, the private sector is expected to finance schemes such as fibre broadband, wind farms and subsea power cables.

Much of the planned investment is by companies in regulated industries including energy and telecoms. Also, more than half of water assets, all the major airports, most ports and all passenger rail rolling stock sit within specialist infrastructure investor vehicles, according to PwC.

The government’s PFI scheme, once used extensively to build schools and hospitals, now accounts for only a small number of new projects.

“Personally, I think the government will struggle to raise the capital, either public or private, to meet its objective,” says Gershon Cohen, global head of infrastructure funds at Aberdeen Standard Investments, one of the largest managers of pension fund capital invested in public-private partnerships. He cites consumer resistance to higher user charges and taxes.

Investors need political and fiscal stability and the rule of law, Mr Cohen adds. “Right now, I don’t think the UK is in a very good place, the main barriers being a lack of political and economic confidence.”

Nick Davies, associate director of the Institute for Government, says the UK needs a more integrated approach. “To realise the full, transformational potential of HS2, you have got to think about the new stations, the housing to be built around those, and hospitals and schools. We have never had that.”

He is optimistic, however, about the National Infrastructure Commission, created by the government to recommend long-term priorities that can command cross-party support. It is due to publish its assessment of what the UK needs for the next 30 years in the summer.

Infrastructure investors are mostly pension funds, life insurers, sovereign wealth funds and other funds acting on behalf of them, looking for long-term investments that provide a steady income stream.

“Private sector investment adds capacity because the government’s balance sheet is constrained, but it also brings private sector skills,” says Andy Rose, chief executive of the Global Infrastructure Investor Association. “You tend to have more consistent investment throughout the cycle.”

What investors need from government, Mr Rose says, is clarity on priorities and the models of procurement it will support. He adds that the private sector needs to show evidence of how well assets have performed.

KPMG’s Mr Threlfall says the main benefit of private capital is “the multiplier effect” on our ability to invest in this country’s future. “We know that public finances are tight,” he says. “If we remain constrained, the country will be much the poorer for it 30, 40 or 50 years out.”