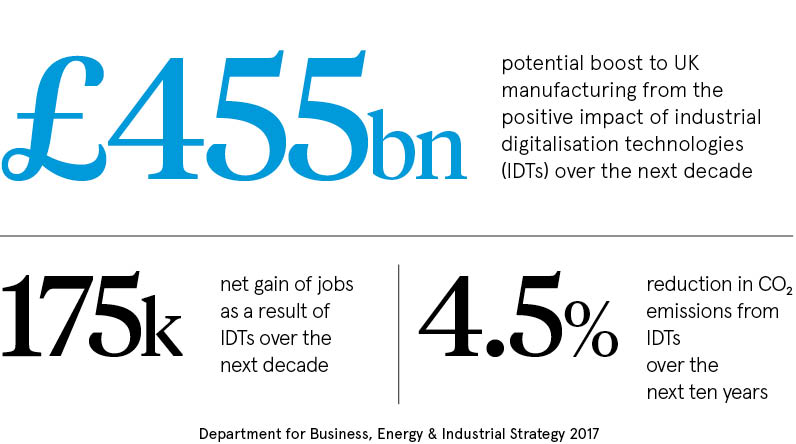

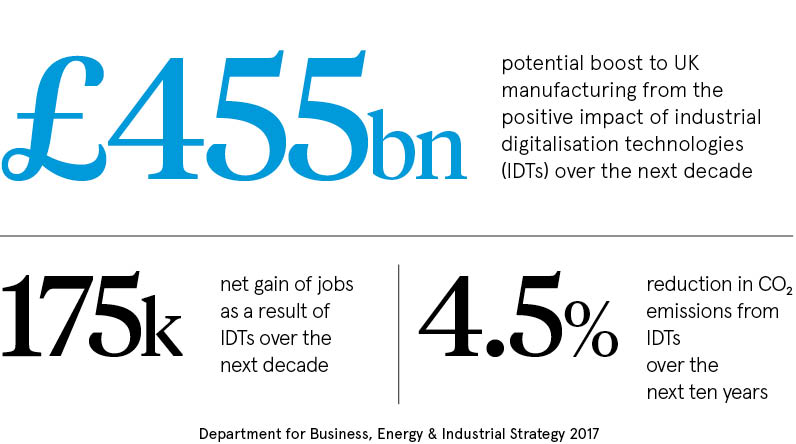

Industry 4.0, or the fourth industrial revolution, describes a new age of digitally enabled manufacturing whereby computers can control automated production lines. The vision of the potential dividends is compelling.

Artificial intelligence will monitor and improve the physical processes of the factory, even anticipating problems before they occur. New products and processes will be tested virtually so real-world production can begin seamlessly. A network of hub factories around the world will be controlled and upgraded remotely with little need for local human labour.

In short, nations and companies that forge ahead stand to benefit from giant strides in their productivity from Industry 4.0, alternatively known as the smart factory.

While the UK, currently the world’s ninth largest industrial nation, has world-class manufacturers in the likes of Airbus, GlaxoSmithKline and Rolls-Royce, there are concerns that reluctance among many companies to invest means the nation risks falling behind.

The UK’s share of capital investment in output has been low compared with key competitor economies for many decades.

The last annual survey by EEF, the manufacturing trade body, in October warned that investment in plant and machinery dropped to 6.5 per cent of turnover in 2017 from 7.5 per cent during the previous year.

Despite a slight improvement in recent years, the UK is also still lagging behind Germany and France when it comes to manufacturers investing in intellectual property, for example.

In this context, Hennik Research’s last annual manufacturing report painted a relatively optimistic picture of readiness for the smart factory. It found that a quarter of manufacturers are already moving to implement Industry 4.0 in their facilities, while 62 per cent are planning to do so. Two-thirds had made investments in automation in the previous 12 months.

However, Mike Thornton, head of manufacturing at audit, tax and consulting firm RSM, says: “Among our own middle-market clients, we notice there’s a lack of understanding and appreciation of what Industry 4.0 can offer, and how this is going to revolutionise the market. This is a key factor that’s holding back investment.”

Derek Cummings, a director at Protiviti, a global consultancy firm, is concerned that Brexit could temporarily place the UK at a disadvantage in the race for Industry 4.0.

He says: “Unfortunately, until Brexit negotiations are concluded and there is a clearer path forwards in relation to trade deals and potential trade barriers for UK companies, it is difficult for most manufacturers to understand their ability to invest in new plant, equipment, capabilities and technologies.”

The government’s industrial strategy noted last year that the UK is already a world leader in artificial intelligence and it wants to provide help for industry to apply these innovations.

However, Mr Cummings believes rival nations have a clearer vision. For example, China is focused on investment in robotics and recently overtook Japan as the world’s largest industrial robot market.

“Recent estimates suggest that the increased use of industrial robotics is likely to reduce manufacturing labour costs in China, Germany, the US and Japan by 18 to 25 per cent by 2025,” he says.

Mr Cummings believes combining the interpretation of industrial data with the UK’s considerable strengths in service industries is the way to get ahead in Industry 4.0.

But where is the capital for manufacturers to upgrade going to come from? Since the significant amounts of cash are needed to upgrade facilities for Industry 4.0, equity risk capital will have to play an important role. Manufacturing attracted 17 per cent of all private equity in 2016, according to the BVCA, the industry body, up from 11 per cent in 2014.

However, the inherent complexity of the transformation may mean the UK’s shortage of “patient capital” could prove problematic.

David Petrie, head of corporate finance at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, explains: “The issue is not around the number of businesses supported, rather that there is a gap in financing where a product cannot be delivered within five to seven years. Investment with a longer time span than the typical three-to-five-year benchmark used by private equity and venture capital funds is lacking.”

The key to getting more investment in innovation will be from government and private sector partnerships

Mr Petrie says the proposed state national investment fund should play a role as a cornerstone investor in innovative manufacturing projects, which should in turn help seed private investment further down the line.

“The key to getting more investment in innovation will be from government and private sector partnerships,” he says. “For example, there must be an effort to support the provision of financial advice to companies raising expansion or scale-up capital.”

Idinvest Partners, a pan-European private equity and venture capital firm with €8 billion under management, says institutional investors themselves may have to innovate to play a greater role. Sylvain Makaya, partner at Idinvest, says this is what the firm has tried to do with its SME Industrial Assets (ISIA) fund.

The unusual, specialist structure aims to finance the modernisation of production equipment for small and medium-sized manufacturers. The €250-million fund was raised because Idinvest believes the kind of manufacturers that could most benefit from improved machinery and processes often struggle to find the right finance.

Instead of purchasing stakes in the manufacturers, the fund buys assets to be leased back to the companies, which are responsible for their management and maintenance. “It allows companies to optimise their cash management, while benefiting from the latest generation of technology and machinery at a reasonable cost,” says Mr Makaya.

John Stokoe, strategic development adviser at European computer-aided design company Dassault Systèmes, agrees that interest from venture capital and private equity will be key to readying industry for the smart factory revolution. “Private equity investment will grow when increased government investment is realised, especially when government actively encourages partnerships with academia, industry and the investors,” he says.