The concept of asset management has grown up in the infrastructure and transport sectors. In so doing it has generated a raft of concepts and technologies which may seem alien to a chief executive with a track record of improving the fortunes of businesses focused on managing financial assets or IT systems.

To make things even more complicated, any newcomer has quickly to get to grips with terms which even asset managers say are not precisely defined.

Life cycle complexities

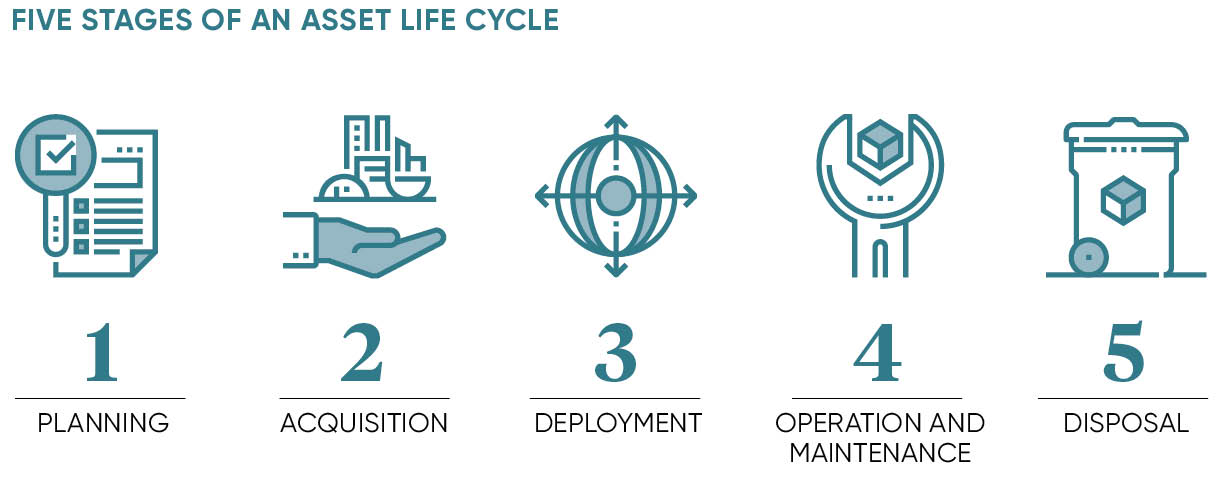

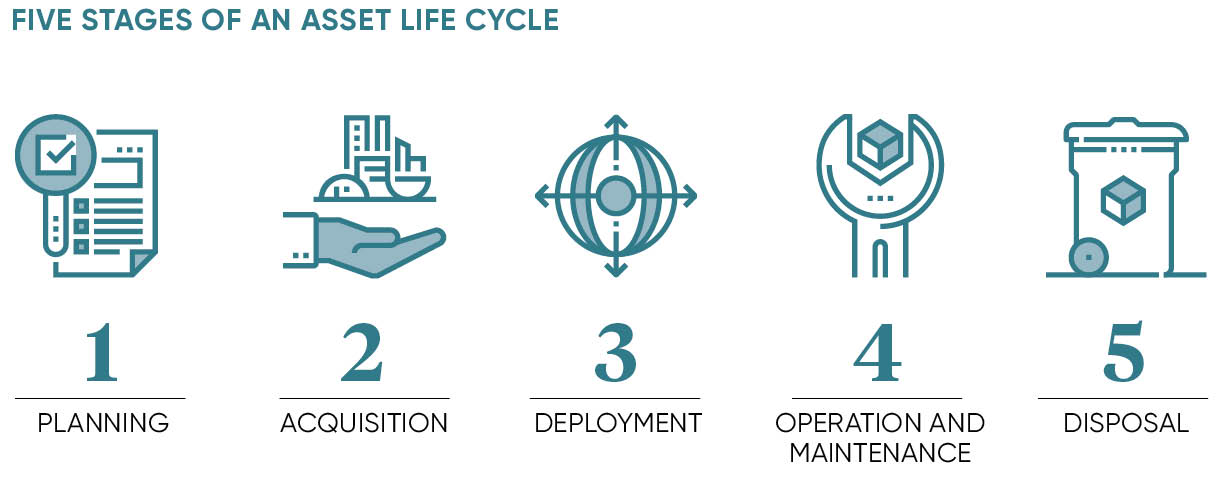

John Woodhouse, chief executive of TWPL and chair of the Panel of Experts at the Institute of Asset Management, says: “There is plenty of lively debate about appropriate terminology and scope for such things as asset life cycles, whole lives and life-cycle activities. At the simplest level, of course, the life cycle concept is clear: for a discrete component that goes through a creation stage, a period of usage and possible maintenance, leading to ultimate disposal or replacement.

“It becomes more complicated, however, when we acknowledge two common realities. The life stages may not be clear-cut, and may even have physical existence periods that span multiple cycles of acquisition, usage and disposal by different organisations.

“Secondly, an asset could have an infinite life if it is defined at a functional system level rather than just a free-standing and disposable item. It may be possible, for example, to sustain a system-level ‘asset’ indefinitely through maintenance and renewal of component elements.

“So the development of asset life-cycle plans or evaluation of investments based on life-cycle costs, and ‘optimising’ horizon for such plans and costs, can be problematic. What horizons should we use in such complex cases? What does life cycle mean in these cases, if anything?”

Mr Woodhouse says the first complex case arises from the differences between seeing the asset from a physical existence viewpoint or from an asset management perspective that is to say responsibility, usage and value realisation. “In developing the [British Standards Institution] PAS 55 standard, we defined life cycle from the asset management perspective – covering the period from recognition of need for the asset through to disposal and any residual risks or liability period thereafter,” he says.

He says this has provided a good catalyst for organisations to consider operations, maintenance and longevity when specifying or investing in assets, and in developing strategic maintenance and renewal plans. “It has certainly helped to break down some of the departmental barriers between engineering design and projects, procurement, operations or asset usage, maintenance or asset care, and renewals or decommissioning,” he adds.

Proving ROI

Richard Edwards, global technical director at AMCL and president of the Institute of Asset Management, says asset management “boils down to making sure that asset investment decisions directly correspond to business results”.

He says: “The conflict for a chief executive or financial director comes when they are under pressure to demonstrate short-term financial results when the asset in question is a building or piece of infrastructure, such as a road, a bridge or part of the rail network, where the relationship between investment and return plays out over several years or even decades.”

According to Mr Edwards, justifying this investment comes down to articulating risk effectively – what could happen in the long term if spending is withheld and what the ultimate cost could be.

Chief executives often have a shorter tenure than the assets that are such a core part of businesses

“Increasingly, we are able to define this risk in a way that decision-makers can understand through more effective and consistent measurement of an asset’s condition, and also much more accurate forecasting of how it will perform over time. This in turn enables chief executives to identify what the financial and organisational consequences would be for the business,” he says.

Chief executives often have a shorter tenure than the assets that are such a core part of businesses involved in the running of infrastructure and transport. What he or she can achieve may be affected by the long-term nature of such systems.

David Millar, joint owner of Morphose, believes the short-term imperative can work side by side with long-term strategies. He is a chartered surveyor by profession who has worked in healthcare, utilities and telecommunications in the UK and internationally.

“A CEO’s ambition is ultimately dictated by the status of a company and its underlying trading as well as operating fundamentals,” he says “In a publicly traded entity, the CEO will always be beholden to the major shareholders’ desires, so the asset management strategy must align closely and achieve their interests, which can restrict change. However, if the business is privately owned, then the situation is slightly more flexible where the owners can take a much longer time horizon on pay-back and intrinsic value.”

According to Mr Millar, while the owner of a private company will still dictate much of the immediate and long-term direction, there is more room for a chief executive to take the reins and make longer-term asset commitments.

He says it is imperative organisations keep a lean portfolio of assets to negotiate the discrepancy between senior management changes, customer demands and available cash, balanced alongside a long-term asset management plan that protects stakeholder interests.

Essentially, this discrepancy has to be approached on a case-by-case basis. No two businesses are the same, with historical circumstances playing a large role in the dynamic. An asset-rich business that is looking to downscale its portfolio will be predisposed for considerable savings and the incumbent chief executive tasked with this will typically have immediate success.

Another challenging area for chief executives is risk because there can be short-term and long-term consequences of taking or not taking risks. According to Oliver Pritchard, a member of Arup’s infrastructure advisory team: “Historically, infrastructure assets and networks have been considered in isolation in terms of risk. However, networks are becoming more and more reliant upon each other, with increasing interdependencies, which necessitate their continued function.”

As pressures increase on owners of infrastructure, transport and utilities to maximise the value of assets, those challenges are likely to concern chief executives and their boards for some time to come.

Life cycle complexities