Environmental pledges are everywhere, but where’s the social action? One US startup believes it has the tool kit to allow businesses to show they are rooting out poverty in their workforces

Businesses know they need to be purpose-led to reflect the environmental and social values their customers and investors hold dear. This means they’re now starting to move beyond net-zero pledges to providing assurance that their goods and services are provided through a workforce that is treated well.

Nevertheless, the gap between environmental and social action is huge. Even though ending poverty is the first priority for the United Nations’ Sustainable Development agenda for 2030, more than half (53%) of FTSE 100 companies failed to mention the word poverty in their annual reports for 2019 to 2020, according to research from think tank Social Market Foundation. It claimed it was a strange omission, prompting an accusation that big business is ignoring the ‘S’ in ESG.

Part of the reason for the disconnect between seeing poverty as an issue, and then pledging action, could be that boards have traditionally not had proven, standard research methodologies and metrics to detect the problem and measure improvements.

Even the official definition of poverty can be restrictive. It has traditionally been applied to those living under the World Bank’s threshold of $1.90 (£1.61) a day or, from this autumn, $2.15 per day. Based on 2017 data, the bank reveals just under 700 million people qualify as living in poverty.

But looking at a person’s life through only a financial lens misses the fuller picture. A worker can be above the poverty line but might have a large family, perhaps with sick parents, unemployed siblings and children to send to school, all on a wage that technically takes them out of the official definition of poverty.

A new approach to poverty

It was to get a more comprehensive picture of poverty and living standards that researchers at the University of Oxford designed the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) which has been adopted by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and is now available to businesses through a spinout called Wise Responder. Rather than rely solely on income, the new questionnaire-based approach relies on many criteria, such as quality of housing, food availability, access to education, healthcare and security. When these more comprehensive factors are included, it becomes clear that poverty is far deeper entrenched than the headline figures would suggest.

When the MPI was applied to three-quarters of the world’s population in 109 developing regions in 2021, one in five were found to be living in multidimensional poverty. The World Bank figure of 700 million living in poverty was nearly doubled to 1.3 billion people.

For Jamie Coats, CEO of Wise Responder, the figures came as little surprise. In his work with many large companies that want to do the right thing by their employees, he reports multidimensional poverty is far higher than boards may have originally thought.

There aren’t standards in social data. We’ve seen environmental data get a lot better, but social data has fallen behind

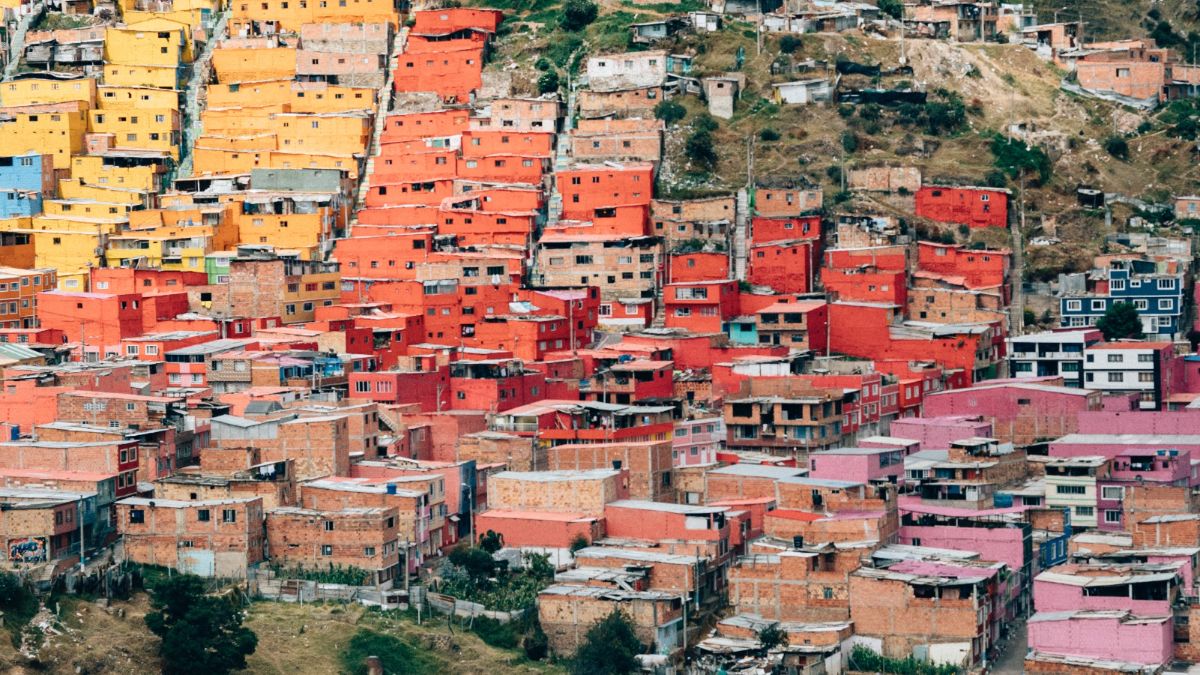

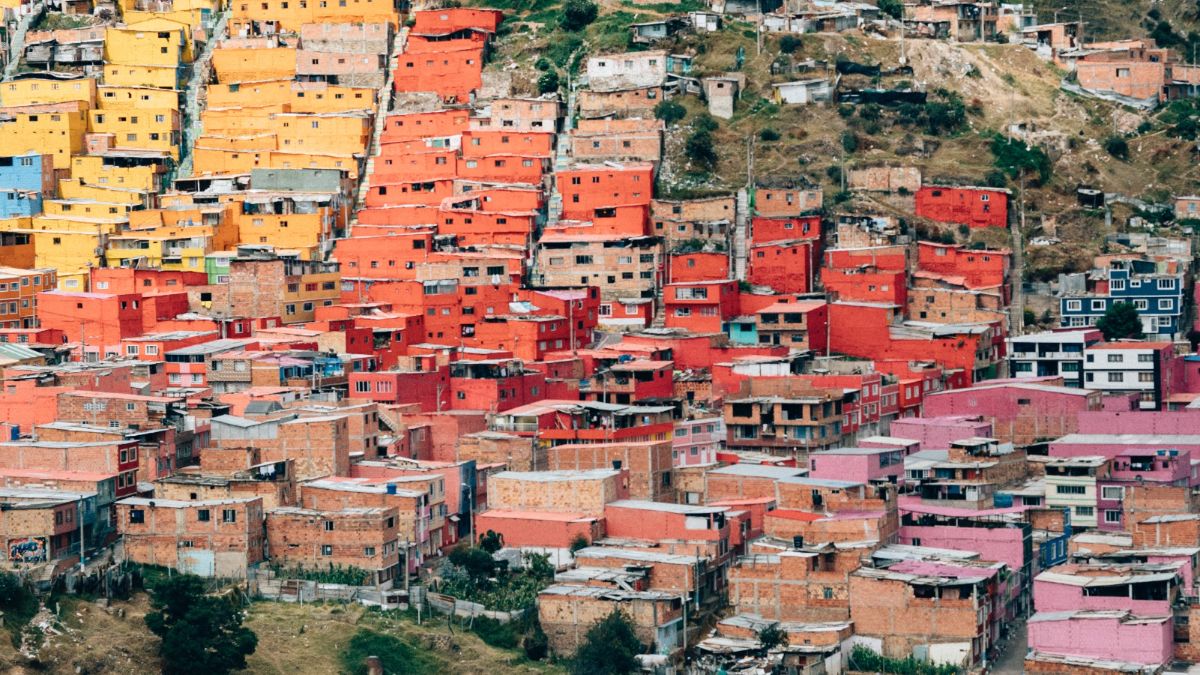

“We’re working with a group of companies across Latin America, including global Fortune 500 companies, that want a well-motivated workforce,” he says.

“Our data shows that across Central America and parts of Latin America, the average rate of multidimensional poverty for companies in the agricultural and beverage industries is around a third of their employees. So, a significant amount of the population is struggling, and that impacts their business.”

By addressing the issue and establishing where a business can improve its workers’ situation, Coats reveals companies can show they care, and that has a significant impact on brand image, as well as employee morale.

“Everybody’s talking about purpose and we’ve seen with companies that help specific individuals, it’s created an esprit in the business by showing that it has an authentic purpose,” he says. “Employees show a lot of gratitude when companies take action and that is very good for loyalty.”

Measure and improve

The data from Wise Responder not only shows areas where multidimensional poverty has been recorded but also highlights areas where the business may be able to help. For example, debt problems can potentially be dealt with through financial advice, and access to healthcare could be improved through company-wide health insurance schemes.

There are areas where a company cannot make an impact on its own and for these larger projects, such as improving schools and sanitation, companies can work in partnership with one another, as well as with local governments and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Although it is early days, there are already signs that this can work well when all parties share the same data.

“We have a partner in Costa Rica, called Horizonte Positivo, which is a business-led coalition of 70 companies with approximately 300,000 employees,” says Coats.

“They discovered that between them they employ just under 10% of the multidimensionally poor people who live in Costa Rica. They have now launched thousands of actions, whether that’s looking at providing education, health care, help with refinancing debt, or home improvements. That coalition of companies is now also working with a set of NGOs that can help supply and support those issues.”

Helping with investment

This not only improves worker conditions but is also proving to be a way of showing investors that a business takes identifying and dealing with poverty in its workforce seriously.

“There are now trillions of dollars that are targeted to ESG but there are just too few quality vehicles to take those funds and then report back on change,” says Coats

“The financial markets are saying, if you can come to us with data, we will have a better conversation about capital allocation. That means investing in social data, alongside environmental data, gives a business something they can literally take to the bank. Citigroup, for instance, has made a $500bn commitment to underwrite sustainable loans based on social indicators. One of the challenges around all this is that there are no standards in social data. We’ve seen environmental data get a lot better but social data has fallen behind.”

Ultimately, Coats believes social indicators for poverty will begin to catch up with those for environmental impact, so businesses will be able to show they have taken action to deal with poverty in their business and its supply chain. This could well lead to a kitemark that companies will be able to display, to reassure consumers and investors they are acting on their shared values of treating people decently.

For those who don’t currently use social measures, his advice is for an executive to go out and look beyond wage levels and check out themselves how workers are living. Do they live in decent housing, can their children go to school, are they healthy, do they get enough food, are there hospitals they can use and do they suffer discrimination?

For those who can’t get out and see workers’ home conditions, here’s a tip. Walk around the canteen at one of your company’s bases and just ask people if the lunch they are currently enjoying will be their only meal of the day. Feedback from executives from large, global companies has so far been that most are surprised by how many rely on the work canteen for their main, often only, meal of the day.

Just following a tick-box exercise of ensuring wages are above the World Bank’s lowest limit would never show this social aspect of multidimensional poverty that is more prevalent than executives realise, until they commit to measure it, and take action.

Related articles

Environmental pledges are everywhere, but where’s the social action? One US startup believes it has the tool kit to allow businesses to show they are rooting out poverty in their workforces

Businesses know they need to be purpose-led to reflect the environmental and social values their customers and investors hold dear. This means they’re now starting to move beyond net-zero pledges to providing assurance that their goods and services are provided through a workforce that is treated well.

Nevertheless, the gap between environmental and social action is huge. Even though ending poverty is the first priority for the United Nations’ Sustainable Development agenda for 2030, more than half (53%) of FTSE 100 companies failed to mention the word poverty in their annual reports for 2019 to 2020, according to research from think tank Social Market Foundation. It claimed it was a strange omission, prompting an accusation that big business is ignoring the ‘S’ in ESG.